Governments lie.

That's one of the first things I tell my freshmen: governments lie. Not always, but often enough you need to always be aware of the possibility. Paul Roberts gets into that territory when he talks about James Jesus Angleton, and stories within stories, and false trails, and 9/11. Why was the unofficial Saudi funding connection classified? It's not like anyone who knew anything about Al Qaeda didn't know about contacts in the royal family, including high-ranking people in the government. It doesn't prove they ordered it. It doesn't even prove that they knew about it. Money is fungible.

The next interesting question, for me, is why are these documents declassified now? Is it to remind people of Bush, and tar the Republicans? That feels like a stretch. Is there another connection, and this is supposed to lead us away from it? Or to it? Roberts claims the purpose is to reinforce the main story--highjackers, airplanes, surprise, etc.--while pointing to an irrelevant financing channel. He seems to want us to believe 9/11 was, at least in part, an inside job. That's a logical leap I'm unwilling to make. While governments lie, in the long run they aren't very good at it. There would have to be too many people involved to keep a secret this large for this long. It's easier to imagine colossal incompetence, at several levels, followed by a lot of mutually-supporting CYA.

Will we ever have a clear picture of everything that happened on 9/11? Probably not. But as people grow older, and confess, and reveal their sins, we'll know more. As copies of records are declassified, or leaked, or stolen, we'll know more. As other countries reveal what they know, we'll know more. Given time, we'll probably have a better picture of the mix of crime and incompetence. It won't be perfect. History is never perfect. But we'll probably have a more complete picture than we have now.

And whatever is the truth, it probably won't be able to compete with the myths.

Is the Saudi 9/11 Story Part Of The Deception? -- Paul Craig Roberts - PaulCraigRoberts.org

25 July, 2016

Contingency--or why most Americans don't speak French

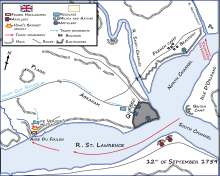

Sometimes bureaucracy is not a problem. Sometimes it solves previously unsolvable problems. Sometimes, it changes the world. Twenty minutes outside the French-Canadian city of Quebec changed the course of the Seven Years' (French and Indian) War. And bureaucracy made it possible for the English to be there, when they needed to be there, to launch the decisive blow.

For the British it was part of the "Annus Mirabilis", but miracles don't just happen. The British Navy had slowly, systematically, mapped the treacherous waters of the St. Lawrence. They intercepted French fire ships and ran them aground. They probed for a landing site, and failed. But eventually they found one, upriver at the base of a bluff. A small French force was defeated, and the British moved up the the plains

of Abraham. The French Army set up to face them. The British Army were in no position to retreat. They would either win, or die.

The French troops outnumbered them, but they hadn't finished training or integrating local troops into the professional army. They were worn down. An while skirmisher lines inflicted casualties, the main body of British and Colonial troops were pros. They held their ground. They followed their orders. They wanted to lead the main body of the French forces to come to them.

The French obliged. The British had double-loaded their muskets, to deliver twice the firepower. But it was a trick they could only use once. They had to wait in place as the French fired, and again, and again, moving forward the whole time. But the British were regulars. This is what they trained for.

Finally the French were close enough to feel the full effect. Call it thirty yards. On command, the British forces fired as one, moved forward through the smoke, reloaded and fired again. Two hundred forty seconds. The French line collapsed, and the survivors began to retreat to the city. Both sides lost their commanding generals in that volley. Both became more disorganized. But the French were in shock, and the British advanced to positions where they could maintain the full siege of the city. Without a source of supplies, without a commanding general, the French eventually surrendered.

The war wasn't over for another year, but the tide had clearly turned. And that's why the eastern side of North America remained British, and eventually American. It may even have contributed, a little, to the willingness of the French to sell the Louisiana territory, fifty years later. And when a student tells me that violence never settles anything, I tell them to read history. There's luck, and preparation. There's friction. But brief moments can change the world.

America Was 20 Minutes Away From Being French - The Daily Beast

24 July, 2016

It always helps to define your terms.

The link below is to an interesting on how to portray and analyze. It is a good step in a useful direction. A common vocabulary would facilitate communication and threat estimates among states, between organizations, and within them. It would facilitate the academic research, too. To deal with a problem, first you have to identify it, and then you need to be able to talk about it. If you can't do the second, you probably still have some problems with the first.

That said, I don't find this iteration to be perfect. What is? Focusing on "violent extremism" rather than "terrorism" is a good idea. "Terrorism" has too much baggage. I'm not sure we could find a consensus on what constitutes "extremism," though. Can it include actions by official representatives of states? Must the target be innocent, or civilian (the two are not the same)? Can a drone strike, or an attack by Special Forces, be characterized as "violent extremism"? Violent, definitely. But some of them SF guys seem pretty extreme, too.

Not assuming the religious angle is probably a good idea. But does it have to be political? If so, how political? I don't include an act of a Lone Wolf that has no more connection than an after-the-fact claim of responsibility to be the same as someone who is inspired--Phil Walter's got that right. But should we include the loser who aims to be playing suicide-by-cop the same as someone who thinks (whether he's right or wrong) that his act will contribute to a desired political outcome? It seems that some serial killers could be violent extremists, but certainly not all. We could include the self-motivated murderers of abortion doctors, but some are "saving babies" while others want to change the law, and most probably hold a mix of motives.

Making a particular religious orientation optional is useful. People with different orientations (or none at all) may well behave differently. Typing could be useful for profiling, and making comparisons. But should politics be optional? I don't think so. The "psycho killer" is different in kind, not degree.

Toward a Common Lexicon of Violent Extremism - Lawfare

That said, I don't find this iteration to be perfect. What is? Focusing on "violent extremism" rather than "terrorism" is a good idea. "Terrorism" has too much baggage. I'm not sure we could find a consensus on what constitutes "extremism," though. Can it include actions by official representatives of states? Must the target be innocent, or civilian (the two are not the same)? Can a drone strike, or an attack by Special Forces, be characterized as "violent extremism"? Violent, definitely. But some of them SF guys seem pretty extreme, too.

Not assuming the religious angle is probably a good idea. But does it have to be political? If so, how political? I don't include an act of a Lone Wolf that has no more connection than an after-the-fact claim of responsibility to be the same as someone who is inspired--Phil Walter's got that right. But should we include the loser who aims to be playing suicide-by-cop the same as someone who thinks (whether he's right or wrong) that his act will contribute to a desired political outcome? It seems that some serial killers could be violent extremists, but certainly not all. We could include the self-motivated murderers of abortion doctors, but some are "saving babies" while others want to change the law, and most probably hold a mix of motives.

Making a particular religious orientation optional is useful. People with different orientations (or none at all) may well behave differently. Typing could be useful for profiling, and making comparisons. But should politics be optional? I don't think so. The "psycho killer" is different in kind, not degree.

Toward a Common Lexicon of Violent Extremism - Lawfare

21 July, 2016

Fun with graphs

I've been reviewing basic comparative data for the foreign policy class. I may have stumbled on a reason the Republicans (and Trump) have been doing so well--or maybe any cause-effect relationship is in reverse. In any case,

I think I'd like to visit Iceland.

In the World Values Survey, there's more evidence of the US has been shifting: from more traditional and more self-expressive to less traditional but also less self-expressive. It's quite a jump from 2008

to 2015, but by no way unique. Also check out South Africa, Ukraine, and Hong Kong, among others.

What's at all mean? I don't know. But it's fun to dig around. If you'd like to take a look at the World Values Survey, you can find it at http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSContents.jsp

I think I'd like to visit Iceland.

In the World Values Survey, there's more evidence of the US has been shifting: from more traditional and more self-expressive to less traditional but also less self-expressive. It's quite a jump from 2008

to 2015, but by no way unique. Also check out South Africa, Ukraine, and Hong Kong, among others.

What's at all mean? I don't know. But it's fun to dig around. If you'd like to take a look at the World Values Survey, you can find it at http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSContents.jsp

17 July, 2016

The Rise of the Internet: A Personal View

Several key points in my life were defined, in part, by the internet. You might say I grew up with it. I certainly wouldn't have been the same person without it. At key points, changes to the internet opened new doors just as I needed them. I've been very lucky.

I graduated from high school in June 1976. In August 1976, the internet was born. At the end of that month I began my Freshman year at what was then called the University of Missouri-Rolla. It was the science and technology school--the state's closest equivalent to MIT. And it was connected to the ARPAnet. I took my first computer science course, learning Basic and compiling programs on punch cards. It was also the first time I had seen dedicated computer labs--rows of terminals, facing the walls, with dot-matrix printers. Another lab had a "microcomputer" about six feet tall, among other things. The mainframe--which processed the cards--filled a room so large I don't recall ever seeing the far side of it. Since I figured I was majoring in the sciences I bought a personal calculator. It could add, subtract, multiply, and divide. It cost me $300 dollars (in 1976 dollars). One of my professors was envious because the year before he'd spent ten times as much for a tabletop calculator with the same capabilities.

I loved that computer lab, and while in retrospect I couldn't do much more than play Zork and Star Trek it was my favorite spot on campus. We did have BITnet (which used the excess computer time--it was called what it was Because It's There), but email was a hassle--and who would you send it to?

Aside from that lab I was pretty much miserable my Freshman year. It gradually dawned on me that I didn't really want to be a physicist or an engineer, and those were pretty much the options at Rolla. So I left abruptly, half way through my third semester, and eventually went to the St. Louis campus to "find myself". I remember looking through the schedule, purposely ignoring any liberal studies or graduation requirements, and signed up for anything that seemed interesting. I had no idea what sociology was, but it sounded cool, so I took it. I was always interested in current events, so I signed up for intro to international relations. I eventually ended up double majoring in political science and sociology, with a shared concentration in IR that I put together for myself. I was having a lot of fun. I remember sitting in the IR class, watching the professor and thinking--I want to do what he's doing; I could do that for the rest of my life. But I was also going home every night to live with my parents, and that began to cramp whatever little style I had.

(It was also at UMSL that I saw my first video game--Asteroids, packaged in a tall fiberglass tower shaped to look like a mid-1970s version of what "21st-Century" furniture might be. It wouldn't have been out of place on the bridge of the Starship Enterprise.)

So I moved on to the main campus: University of Missouri-Columbia. There were plenty of classes I liked, plenty of people I liked, and I learned some more things about myself. It was also here that I clearly remember seeing the first computer terminal in a home. The father of a girl I knew was in the computer science department, and the terminal, complete with CRT display, was set up on a desk in the corner of the living room. He was fully plugged in to the campus, and the internet, with a dedicated T1 line. It was fast. It was global. And I wanted something just like it.

Graduate school started with a card catalog and ended with a terminal. My dissertation was started on a typewriter and ended on a Mac. A 128? A 512? 128, I think. And modems working at a blinding 1200 bps. And Compuserve. And GEnie. And Byte. And the Well. I had conversations with some of my favorite SF authors, because they were of course among the early adopters. There was a guy who I hadn't heard of before, but he was very engaged with fans and he was developing a new TV show called "Babylon 5" that sounded like it could be very good. And AOL was mailing CD-roms and disks to everyone, simplifying the email and internet connections. Pages would have frozen color images, occasionally, but messaging was through email and bulletin boards.

Two problems: a fast modem was still around 2400 bps, and the internet providers were charging by the second. So people developed write-arounds, to download everything at once, disconnect, and when you had all your posts read and written it would reconnect, upload everything, and log off.

I was in one of my temporary teaching jobs, in Indiana, when I got involved with GEnie. There was a bulletin board on earth religions I found interesting. Not my usual kind of stuff, but the people were smart and civil and I'd already had my fill of flame wars. There was one girl in particular: she was smart, she was creative, she would point out new and interesting things I hadn't thought of myself. I didn't know much about her, but I knew I liked her. And then I got an email from her. To this day, I remember the full text of the message:

Subj: Hello.

And the rest was blank. That happened sometimes. Between the networks and the download/upload software things could get lost. I thought about it for a while, and I wrote back. I complemented her for the brevity of her message, and we started a conversation. The more I learned about her, the more I liked her. A lot. I started to think I might actually meet her some day. I tried to be honest with her: who I was, my flaws, my dreams. Things I hadn't told the people around me. I was a near-complete introvert, but somehow I _wanted_ her to know these things. And she was honest with me.

(Note that this was BEFORE on-line dating sites. Before cyber predators became a topic for conversation. Before complete jerks set up false profiles on line. It was also before you could attach a photo to email, so neither of us knew what the other looked like, other than how we described ourselves. And each of us knew even an "honest" self-description was biased by how we saw ourselves, and that wasn't the same as reality.)

The internet and I were completely in-sync. It was words, and I was good with words. And they weren't even _spoken_ words. I could revise whatever I sent before I sent it. We didn't have body language, or fashion, or any of those visual cues we use to judge one another. I couldn't trip over my own feet. Eventually we started with phone calls, but at this stage neither of us would have recognized the other's voice. It was simple enough even _I_ could do it. Five years earlier, and we couldn't have found one another. Five years later, and I wouldn't have had the nerve to try.

Like I said: lucky. Or fate, take your pick. As you probably guessed, we eventually married. The wedding (already scheduled) was the first weekend of my new job, a faculty position I've held for twenty years.

But one last story. We were talking by phone now, as well as all the internet connections. I'd finished the adjunct job in Indiana, but I was unemployed and she lived in North Carolina and I didn't have a way to get there. We still wouldn't have recognized each other on the street. I suppose we could have snail-mailed photos to each other. I just hadn't thought about it. Or I was afraid she'd see a picture of me and somehow things would go wrong. But I had a political science conference to attend in D.C., and some job interviews. I was surrounded by friends--and there was a train to North Carolina. She and I arranged for me to visit for a few days. If she didn't feel comfortable, I could check into a motel for a couple of days. If it was OK, I'd stay with her. Maybe sleep on the couch. I was so anxious about this meeting that I was probably the last one off the train. And when I stepped off, there was this girl in the center of the platform. She had a smile that melted all the fear. She glowed--at least that's how I remember it. And she was holding a sign: "IT'S ME". I hugged her so long and so hard that we popped a lens out of her glasses. I spent the night at her place. I wasn't on the couch.

Each step of the way, the internet opened a door. Just a bit more each time. Just enough to manage the transition. Netscape and the Web took off about the same time as Susan and I got together in the "real" world. So when I think about the development of the internet, it's personal. In a sense, we grew up together. At each point, what I saw was then the cutting-edge of technology. It was always clearly better than anything I had seen before. It opened doors. And I was in just the right place to take advantage of it.

How the internet was invented | Technology | The Guardian

I graduated from high school in June 1976. In August 1976, the internet was born. At the end of that month I began my Freshman year at what was then called the University of Missouri-Rolla. It was the science and technology school--the state's closest equivalent to MIT. And it was connected to the ARPAnet. I took my first computer science course, learning Basic and compiling programs on punch cards. It was also the first time I had seen dedicated computer labs--rows of terminals, facing the walls, with dot-matrix printers. Another lab had a "microcomputer" about six feet tall, among other things. The mainframe--which processed the cards--filled a room so large I don't recall ever seeing the far side of it. Since I figured I was majoring in the sciences I bought a personal calculator. It could add, subtract, multiply, and divide. It cost me $300 dollars (in 1976 dollars). One of my professors was envious because the year before he'd spent ten times as much for a tabletop calculator with the same capabilities.

I loved that computer lab, and while in retrospect I couldn't do much more than play Zork and Star Trek it was my favorite spot on campus. We did have BITnet (which used the excess computer time--it was called what it was Because It's There), but email was a hassle--and who would you send it to?

Aside from that lab I was pretty much miserable my Freshman year. It gradually dawned on me that I didn't really want to be a physicist or an engineer, and those were pretty much the options at Rolla. So I left abruptly, half way through my third semester, and eventually went to the St. Louis campus to "find myself". I remember looking through the schedule, purposely ignoring any liberal studies or graduation requirements, and signed up for anything that seemed interesting. I had no idea what sociology was, but it sounded cool, so I took it. I was always interested in current events, so I signed up for intro to international relations. I eventually ended up double majoring in political science and sociology, with a shared concentration in IR that I put together for myself. I was having a lot of fun. I remember sitting in the IR class, watching the professor and thinking--I want to do what he's doing; I could do that for the rest of my life. But I was also going home every night to live with my parents, and that began to cramp whatever little style I had.

(It was also at UMSL that I saw my first video game--Asteroids, packaged in a tall fiberglass tower shaped to look like a mid-1970s version of what "21st-Century" furniture might be. It wouldn't have been out of place on the bridge of the Starship Enterprise.)

So I moved on to the main campus: University of Missouri-Columbia. There were plenty of classes I liked, plenty of people I liked, and I learned some more things about myself. It was also here that I clearly remember seeing the first computer terminal in a home. The father of a girl I knew was in the computer science department, and the terminal, complete with CRT display, was set up on a desk in the corner of the living room. He was fully plugged in to the campus, and the internet, with a dedicated T1 line. It was fast. It was global. And I wanted something just like it.

Graduate school started with a card catalog and ended with a terminal. My dissertation was started on a typewriter and ended on a Mac. A 128? A 512? 128, I think. And modems working at a blinding 1200 bps. And Compuserve. And GEnie. And Byte. And the Well. I had conversations with some of my favorite SF authors, because they were of course among the early adopters. There was a guy who I hadn't heard of before, but he was very engaged with fans and he was developing a new TV show called "Babylon 5" that sounded like it could be very good. And AOL was mailing CD-roms and disks to everyone, simplifying the email and internet connections. Pages would have frozen color images, occasionally, but messaging was through email and bulletin boards.

Two problems: a fast modem was still around 2400 bps, and the internet providers were charging by the second. So people developed write-arounds, to download everything at once, disconnect, and when you had all your posts read and written it would reconnect, upload everything, and log off.

I was in one of my temporary teaching jobs, in Indiana, when I got involved with GEnie. There was a bulletin board on earth religions I found interesting. Not my usual kind of stuff, but the people were smart and civil and I'd already had my fill of flame wars. There was one girl in particular: she was smart, she was creative, she would point out new and interesting things I hadn't thought of myself. I didn't know much about her, but I knew I liked her. And then I got an email from her. To this day, I remember the full text of the message:

Subj: Hello.

And the rest was blank. That happened sometimes. Between the networks and the download/upload software things could get lost. I thought about it for a while, and I wrote back. I complemented her for the brevity of her message, and we started a conversation. The more I learned about her, the more I liked her. A lot. I started to think I might actually meet her some day. I tried to be honest with her: who I was, my flaws, my dreams. Things I hadn't told the people around me. I was a near-complete introvert, but somehow I _wanted_ her to know these things. And she was honest with me.

(Note that this was BEFORE on-line dating sites. Before cyber predators became a topic for conversation. Before complete jerks set up false profiles on line. It was also before you could attach a photo to email, so neither of us knew what the other looked like, other than how we described ourselves. And each of us knew even an "honest" self-description was biased by how we saw ourselves, and that wasn't the same as reality.)

The internet and I were completely in-sync. It was words, and I was good with words. And they weren't even _spoken_ words. I could revise whatever I sent before I sent it. We didn't have body language, or fashion, or any of those visual cues we use to judge one another. I couldn't trip over my own feet. Eventually we started with phone calls, but at this stage neither of us would have recognized the other's voice. It was simple enough even _I_ could do it. Five years earlier, and we couldn't have found one another. Five years later, and I wouldn't have had the nerve to try.

Like I said: lucky. Or fate, take your pick. As you probably guessed, we eventually married. The wedding (already scheduled) was the first weekend of my new job, a faculty position I've held for twenty years.

But one last story. We were talking by phone now, as well as all the internet connections. I'd finished the adjunct job in Indiana, but I was unemployed and she lived in North Carolina and I didn't have a way to get there. We still wouldn't have recognized each other on the street. I suppose we could have snail-mailed photos to each other. I just hadn't thought about it. Or I was afraid she'd see a picture of me and somehow things would go wrong. But I had a political science conference to attend in D.C., and some job interviews. I was surrounded by friends--and there was a train to North Carolina. She and I arranged for me to visit for a few days. If she didn't feel comfortable, I could check into a motel for a couple of days. If it was OK, I'd stay with her. Maybe sleep on the couch. I was so anxious about this meeting that I was probably the last one off the train. And when I stepped off, there was this girl in the center of the platform. She had a smile that melted all the fear. She glowed--at least that's how I remember it. And she was holding a sign: "IT'S ME". I hugged her so long and so hard that we popped a lens out of her glasses. I spent the night at her place. I wasn't on the couch.

Each step of the way, the internet opened a door. Just a bit more each time. Just enough to manage the transition. Netscape and the Web took off about the same time as Susan and I got together in the "real" world. So when I think about the development of the internet, it's personal. In a sense, we grew up together. At each point, what I saw was then the cutting-edge of technology. It was always clearly better than anything I had seen before. It opened doors. And I was in just the right place to take advantage of it.

How the internet was invented | Technology | The Guardian

16 July, 2016

Nationalists and Globalists

Jonathan Haidt (and the researchers he cites) get it: the critical split, especially in the Western democracies under threat of massive immigration is not primarily about social classes, or races, but about visions of the future. It's about Globalists versus Nationalists. Globalists tend to assume Nationalists are racist homophobes who want a world of white privilege, and some are. Nationalists tend to assume Globalists are naive elitists who want to erase borders, and some are. In my field, the traditional distinction between Realists and Liberals reflects this split somewhat. It was easier to manage when people had much less direct contact with one another (and is reflected in the long-standing American mistrust of the Foreign Service). Now we are in one another's faces. We withdraw to Fox News and MSNBC to recharge, and then go back to the fight. For example: Rob Gannon, I think you are more of a Nationalist, but one who recognizes the Globalists make a few good points. As for me, my Heart is with the Globalists, but my Head has accepted that for today and the near future, the World is Nationalist. Not everyone accepts the idea of universal human rights, and quite probably never will. Our "common humanity" is more like a matter of degree. And there's a big advantage on the Nationalist side: many more people are willing to kill and die for their nation than are ever willing to carry a gun for free speech and multiculturalism.

And how moral psychology can help explain and reduce tensions between the two.

06 July, 2016

Getting past either/or

There are people who want us to think in dichotomies: left/right, good/evil, republican/democrat, proletariat/bourgeoisie, christian/atheist, shi'a/sunni, terrorist/government... Have I pushed anybody's buttons yet? If I have, you might be part of the problem. Or not--I don't want to set up just another dichotomy. Just remember that in order to work this civilization requires talk, criticism, testing, and compromise. And there are some people who, for reasons of profit or reasons of ideology or reasons of faith, would rather not live in this civilization. But for all its faults, this Enlightenment civilization has tended in the direction of greater freedom, greater personal power, greater wealth, greater happiness, better health, and longer life. I personally want to continue living in it, and improving on it. Please don't stand in the way.

DAVIDBRIN.BLOGSPOT.COM|BY DAVID BRIN

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)