06 December, 2009

TSA interrogation

04 December, 2009

Americans to be stationed in Poland

That's the real issue behind the announcement to station American troops and a battery of Patriot missiles on the soil of Poland. One missile battery won't have much real effect, and the troops will be on rotation from Germany, but the symbolic message is there. Yet another "tripwire." Since Russia and Belarus recently held nuclear war games, including a simulated beach landing in Poland, some Poles are happy to get whatever support they can.

02 December, 2009

Obama's speech

Probably the best we could do, under the circumstances. Maintaining the distinctions between the Iraq and Afghan Wars was important. Even more important was setting victory conditions that might be achieved. It is not about making Afghanistan "secure" or "free," it's about providing the breathing space to develop a local government that is willing and able to prevent the use of Afghanistan as a base for training and operating transnational terrorists. With that definition it is possible to declare victory and go home--or learn that no such government is possible, go home, and when necessary blast the terrorist camps (and/or Afghan government) as they emerge.

01 December, 2009

It beats dropping bombs

That's really what's at issue here. A Serbian friend of mine constantly reminded me during the Kosovo War that what NATO was doing was a violation of fundamental legal norms, and while he was right he never quite grasped that his point may be increasingly irrelevant. The norms are changing. What are the new norms, and how will they emerge? An advisory opinion of the ICJ isn't going to settle these issues, but it might have some influence on the debate. Keep watching.

Libson treaty is now in effect

The treaty says that unanimous agreement will still be needed to affect taxes, foreign policy, defence and social security, areas where countries take their sovereignty very seriously. On the other hand, what constitutes "climate change" or "energy security" or "social security?" It looks like what we are getting here--as has been observed about the US Constitution-- is "invitation to struggle."

25 November, 2009

The secret to immortality

Norwegian foreign policy

10 November, 2009

06 October, 2009

What you may think you know is wrong

Juan Cole does a superior job of reminding people of the ten Top Things you Think You Know about Iran that are not True. As a bonus, the comments are generally intelligent and informative. The more I look at the situation, the more it seems to me that the US-Iran relationship doesn’t have to be nearly as tense as it is today. Unfortunately, a single viewpoint has prevailed in the MSM—just like it did before the Iraq War. We all know how well that turned out.

26 September, 2009

Police riot. Crowd is caught in the middle.

Last night, as the G20 had wrapped up, I was about a mile away from the Schenley Plaza "protest," monitoring police bands and getting messages from people at the site. A few observations:

1) There was no formal "protest," per se. A group of people had decided to assemble on the plaza to call attention to what they considered to be unnecessary brutality by the police earlier in the day. It's the sort of thing that happens all the time.

2) Police arrived in masse. Oakland had been witnessing a show of force for the past few days (I know: I regularly drove past long lines of cops in riot gear and watched an apache helicopter fly low over my house.) At least some of the cops were not from Pittsburgh. In fear of a repeat of Seattle, the local "authorities" (and it find it increasingly difficult to use that word) brought in and deputized police from across the country. I know some were some Miami. The scanner reported when a busload of Chicago cops arrived on the scene.

3) A crowd emerged to see the show. The plaza is across from the university library, and a block from freshman dorms.

4) The vast majority of the vandalism (broken windows) in the area was traced back to a single anarchist from California. (It was clear it wasn't a local when he hit the student's favorite diner. I suspect there was student cooperation to find and turn him in, but can't prove it.) He was in custody before nightfall, and before any crowd assembled.

5) A sonic weapon was used: a Long Range Acoustic Device (LRAD), similar to those deployed in Iraq, on ships, and during Katrina. Big-city police departments have been purchasing the LRAD, but this is, to my knowledge, the first time one has been used on a crowd inside of the US.

6) Local tv news was reporting from the scene in the early phases. It was all great theater and it was occurring during the regular 11 pm news broadcast. However, just before the riot control gasses were brought out, the local stations cut away, never to return.

7) On the scanners, before switching to tac frequencies I couldn't monitor, there were repeated references to initiating "hammer and anvil."

8) Crowds were told to disperse, but at the same time were given no place to go. The cops were quite thorough in blocking potential exits. Some people were trapped on open stairwells, with police blocking the top and bottom, while the gas passed through.

9) Some of the cops were very professional. Some of them acted like thugs. One of the high points was when the campus cops refused the outsiders admission to the dorms. It didn't entirely stop them, but it slowed the city (and other) forces and gave people a chance to calm down.

10) Cops were very aware of what might get to the news. I monitored pursuits being broken off for fear that they would be witnessed by news crews.

11) Although people have begun to be released, the police are holding their property. There is some concern that cameras and cell phones will be empty when (and if) they are returned.

12) Most of the city is glad to just get back to normal. Some people are very, very pissed.

24 September, 2009

Irving Kristol

Dead, at the age of 89. Famous as the so-called godfather of neoconservativism, he managed to link the political and ideological tactics of the Trotskyites (where he began) with the deep Jacksonian strain in American political culture. He loved the State, and pushed for its expansion--so long as the right people were in charge. It's no wonder his ideas resonated within the Bush White House.

Give the man his due. He wasn't parroting sound-bites crafted for him by others. He didn't fear a good argument. He knew what he believed and why he believed it. He was more than willing to spell it out to others (for a classic intro to what he believed, see his essay The Neoconservative Persuasion ). While I have never agreed with him on some of his "facts" and most of his values--in particular his disregard for the lives and dignity of the regular people who pay the price for empire--he was a "great" man. Not quite as "great" as Stalin, or Hitler, or Mao--but it wasn't for lack of trying.

15 September, 2009

China: democracy and warlords

A reporter for OpenDemocracy spent the month of August touring China, looking for signs of democratization. He finds more than he bargained for:

Indeed, in interviewing people from various organisations and from very different perspectives, I was struck by a consistent undertone of worry about the prospect of a regime change (even a "colour revolution") along the lines of those in the post-Soviet states in the early 2000s - which culminated in the governing communist or reformed-communist parties being ejected from office. elections China's clear official aim is to ensure that it doesn't make the same mistake. But in a country undergoing rapid change, how much of the political course of events and outcome can the party still control?

But that’s the cities. I imagine most of the conversations were with the intelligensia. Out in the countryside, a far different picture emerges:

In China's northeast, quasi-mafia groups have made entire rural areas their fiefdoms, which they run according to their extensive business interests. In the southeast province of Fujian, similar elite economic groups have established control of villages via local representatives who ruthlessly pursue the groups' private interests with no regard for broader social goals. In the central provinces of Hunan, Henan and Hebei, most evidence I saw showed a clear battle between party operatives and other increasingly powerful groups (from specific clans in one area, to economic or ethnic or social groups in another). Such tense and uneven situations help put in perspective Hu Jintao's emphasis, in the aftermath of the Xinjiang disturbances, on the need to have "one law for everyone".

Lots of luck on that, Hu.

America leads the world

At least, in terms of arms sales. The American share of the market in 2008, according the the Congressional Research Service, was 68.4 percent. Italy was number 2 with 6.7 percent, and Russia number 3 with a drop to $3.5 billion in sales, which is a little less than Italy.

There are advantages to doing this, of course. Increased production lowers unit cost, keeps production lines open without a direct payment from American taxpayers, and can foster dependency on the US for spare parts and maintenance.

Personally, I think we’re underestimating the people we sell to. Iran arranged to keep their American planes flying for a long time after the fall of the shah. Israel helped to develop some of the things we sell ,for gosh sake. There are smart people around the world who might pick up the slack for a client dropped by the US.

14 September, 2009

Sometimes I’m embarrassed to be an American

And REALLY embarrassed to be a teacher. Are people afraid to think?

Charles Darwin film 'too controversial for religious America' - Telegraph

08 September, 2009

03 September, 2009

Magnetic monopoles

A team of European scientists have announced that they have observed, for the first time, magnetic monopoles: things that have only one magnetic pole (a north pole without a south pole, for example). I suppose only a former physics nerd will find this exciting, but I think it's cool.

The possibility of these things was first predicted by Paul Dirac--who also predicted the existence of antimatter--in 1931. So congratulations to professor Dirac!

The key to a successful policy is to do well while doing good

China is buying the dollar equivalent of $50 billion, or roughly 10 percent, of the IMF's first bond sale. The IMF is raising the cash in order to lend to developing and emerging market economies. The Europeans say they will contribute 125 billion euros, about a third of the goal. Brazil and Russia have expressed interest in the sale. To the extent that the IMF is helpful (a debatable point), these are good things. But the sign of a smart policy is that those who do good are also in a position to profit from it.

In addition to improving China's status in the IMF, the interesting point is the purchase is in Yuan (341.2 billion), a currency not traded on global markets, rather than dollars. This fits with a general policy of spreading the yuan. China already has a currency swap deal with Argentina, and has negotiated lending yuan to the central Banks of Malaysia, South Korea, Indonesia, and Belarus in the event of an emergency. While the IMF bonds are denominated as Special Drawing Rights (SDR) the IMF may lend yuan to developing countries, who could start using the yuan as a reserve currency. This encourages the transition from the dollar to SDRs, and a swap of dollars for yuan.

This isn't some sinister conspiracy. It's just good sense, if China has doubts about the dollar.

Preparing for the G-20

Pittsburgh, where I live, is the site of the next G-20 summit. The city is gearing up: the anarchists are organizing (to the extent anarchists ever do); the police (who have a reputation for unwarranted violence) are planning crowd control. The feds are moving in, declaring a no-fly zone over the city, and rumors are that we should expect troops in the street.

Official groups, working to get it all organized, emphasize the economic opportunities: it could be bigger than the Super Bowl, they say. It isn't yet decided just how far the secure zone will extend, so businesses throughout downtown are also being told to plan for the equivalent of a traffic-stopping blizzard.

Susan will be manning the phones, taking reports of police brutality. I'm to be trained as an ACLU legal observer. The hope is that placing observers will keep everybody honest. It's only sensible to hope for the best and plan for the worst.

Looks like this could be interesting.

29 August, 2009

25 August, 2009

Health care: how did we get into this mess?

The Independent Review (Summer 2009) has published a really, really good overview of the development of the American health care system, and a copy is available online.

The Modern Health Care Maze: Development and Effects of the Four-Party System

By Charles Kroncke

Ronald F. WhiteDespite numerous federal interventions that have favored health care providers and insurers, the industry has yet to figure out how to overcome the problems of adverse selection, moral hazard, information asymmetry, and free-ridership. Did it ever make sense to create a health care system in which fourth-party employers purchase insurance for their first-party employees from third-party corporations, which in turn pay second-party providers for health care products and services?

One very important point: a lot of what's been going on is related to the use of tax policy to achieve "social goods," a feature (bug) of the current tax system that almost nobody is willing to do without. Raising that issue would be a really radical approach. And then there's the real truth that nobody wants to face: when the demand for health is unlimited and the supply is limited, somebody is going to be unhappy with how it is distributed.

It doesn't mean we can't do better. It means my definition of better may not be the same as yours, and neither of us agree with the other guy, and somebody is going to lose.

Walking a tightrope

STRATFOR has an interesting article (subscription required) that discusses the China's proposed change in banking regulations. They are changing accounting rules to no longer allow certain subordinated loans to be counted as part of a bank's reserves.

Why should anyone care? Because it's a sign of how nervous the Chinese government is about a growing financial bubble. They need to encourage lending to have any chance of meeting the official goal for growth in GDP. At the same time--and despite the fact that there's already a relatively high 12 percent reserve limit--there's a growing fear that the money that's being going out from banks has been going to projects that aren't likely to pay off. China has its own bubbles, and they're growing. Can they deflate the bubbles without losing growth?

Sounds familiar, doesn't it? Perhaps they should talk to Ben Bernanke.

27 July, 2009

Use it or lose it

A recent Brookings paper discusses the international legal aspects of targeted killing. As you would expect, American policy isn't in sync with the emerging global norm. An idealist might argue that the US is in the wrong (and they have a very strong case under the International Convention on Human Rights); a Realist might argue that the US needs the latitude to kill because it (or somebody--and nobody else is available) has the responsibility to combat enemies of the legal regime that everyone else assumes. The point that I hadn't thought of before is the conclusion that the US might want to be open about what it is doing and assert--as a legal principle--that this is as it should be.

The ultimate lesson for Congress and the Obama Administration about targeted killings is “Use it or lose it.” This is as true of its legal rationale as it is of the tool itself. Targeted killings conducted from standoff platforms, with improving technologies in surveillance and targeting, are a vital strategic, but also humanitarian, tool in long-term counterterrorism. War will always be important as an option; so will the tools of law enforcement, as well as all the other non-force aspects of intelligence work: diplomacy and coordination with friends and allies. But the long-standing legal authority to use force covertly, as part of the writ of the intelligence community, remains a crucial tool—one the new administration will need and evidently knows it will need. So will administrations beyond it.

<snip>

The death of Osama bin Laden and his top aides by Predator strike tomorrow would alter national security counterterrorism calculations rather less than we might all hope. As new terrorist enemies emerge, so long as they are “jihadist” in character, we might continue referring to them as “affiliated” with al Qaeda and therefore co-belligerent. But the label will eventually become a mere legalism in order to bring them under the umbrella of an AUMF passed after September 11. Looking even further into the future, terrorism will not always be about something plausibly tied to September 11 or al Qaeda at all. Circumstances alone, in other words, will put enormous pressure on—and ultimately render obsolete—the legal framework we currently employ to justify these operations.

What we can do is to insist on defining armed conflict self-defense broadly enough, and human rights law narrowly enough—as the United States has traditionally done—to avoid exacerbating the problem and making it acute sooner, or even immediately.

<snip>We stand at a curious moment in which the strategic trend is toward reliance upon targeted killing; and within broad U.S. political circles even across party lines, a political trend toward legitimization; and yet the international legal trend is also severely and sharply to contain it within a narrow conception of either the law of armed conflict under IHL or human rights and law enforcement, rather than its traditional conception as self-defense in international law and regulation as covert action under domestic intelligence law. Many in the world of ideas and policy have already concluded that targeted killing as a category, even if proffered as self-defense, is unacceptable and indeed all but per se illegal. If the United States wishes to preserve its traditional powers and practices in this area, it had better assert them. Else it will find that as a practical matter they have dissipated through desuetude.

Does the US (or someone) have the right to target individuals? In States where the US is not formally at war? Inside the US?

I suspect that someone has to have the job of playing cop in the international system. I don't see anyone but the US who is able and willing to do it. A UN force is a possibility, but it still comes down to great power politics and capabilities. On the other hand, I don't want to give the cops--any cops--the right to target whoever they choose. Even if they start with the best of intentions, that's a structure that corrupts the cop, alientates the community, and kills the innocent.

24 July, 2009

Why I don't expect I'll ever be Secretary of State

..or much of any other government-related position. Stephen Walt gives a list of the 10 Commandments--the 10 "thou shalt not hold or even consider" positions that are considered outside of "acceptable" foreign policy discourse. I've given serious consideration to ALL of them at one time or another. Probably about half of them are things I believe today.

This reminds me of when I was a very young research analyst, and after handing in a report I had out a lot of work into, my boss (for whom I had and still have the greatest respect) returned it with the comment

"Well thought out. Almost certainly true. Don't ever say it again."

I think that was the point I decided I'd get out of professional consulting and focus on the university. University political science departments have their own taboos, but once you get tenure you are less vulnerable to sanction. And officially, at least, every idea is supposed to be considered on its merits--even the "unacceptable" ones.

Taboo Topics on Contemporary Foreign Policy Discourse | Stephen M. Walt

22 July, 2009

Another small step in the right direction

Last month, the Seventh Court of Appeals found that “government must operate through public laws and regulations” and not through “secret law.” Specifically, the Court rejected the claim of the Department of State that it could classify any article as a "defense article," thereby making it subject to export controls. The author of the decision, a Reagan appointee, wrote that to accept the government's claim to act "without revealing the basis of the decision and without allowing any inquiry by the jury, would create serious constitutional problems.”

Is somebody reading the Constitution?

21 July, 2009

It ain't over till it's over

From our friends at the Times:

Iran’s reformist former president Mohammad Khatami called Sunday for a referendum on the legitimacy of the government in the wake of last month’s disputed presidential election, Iranian Web sites reported.

Mr. Khatami’s comments amounted to a bold challenge to Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who has dismissed the opposition’s claims that President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s landslide victory on June 12 was rigged, and has ordered protesters to accept it.

It is unlikely that Iran’s hard-line leaders will accept the referendum proposal. But the fact that Mr. Khatami proposed it at all suggests a renewed confidence within the opposition movement.

Don't get your hopes up. The apparatus of oppression seems quite comfortable supporting the present regime. Besides, we're not talking about liberal democracy here. A "reformist" in Iran is not what most people think it is. The real debate is among members of the elite to determine the inner workings of the Islamic Republic, its relation to the corruption that is endemic to the elite, and how far it will go to maintain the strictest interpretation of the law.

On the other hand, some Islamic Republics are better than others. This situation deserves monitoring.

Bernanke op-ed in the Wall Street Journal

Ben Bernanke wants to assure people that the Fed isn't just throwing money at the current problems, unaware of the long-term impact on inflation.

My colleagues and I believe that accommodative policies will likely be warranted for an extended period. At some point, however, as economic recovery takes hold, we will need to tighten monetary policy to prevent the emergence of an inflation problem down the road. The Federal Open Market Committee, which is responsible for setting U.S. monetary policy, has devoted considerable time to issues relating to an exit strategy. We are confident we have the necessary tools to withdraw policy accommodation, when that becomes appropriate, in a smooth and timely manner.

Gee--is everybody confident now? A few observations:

1) The chairman of the Federal Reserve Board is worried enough about confidence that he chooses to make this statement.

2) He does so in a form that allows no questioning or rebuttal.

3) To the extent that he discusses the tools to contract the money supply, it's all pretty much the same as before. We've learned they aren't nearly as all-powerful as he want us to believe.

4) Bernanke says almost nothing about the international dimension--including foreign exchange and the impact on what has been the world's reserve currency.

5) All these promises miss the political dimension altogether. Are we really to believe that those who have been personally helped by recent policies--bailed out banks, investment houses, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, etc.--are going to sit by and watch the Fed crank up the pain? The relation of Congress and State governments to the stimulus package is similar to that of an addict to cocaine. The American people will want their freebies, and they won't want to pay for them.

I'm supposed to feel more confident after reading this?

09 July, 2009

Rethinking liberal arts

(Reposted at Duck of Minerva)

What does a citizen need to know? What skills and knowledge should we assume in our interactions with others? What makes a person a well-rounded person? The issues go back for centuries, and every so often some suggests modifications to the list of "liberal arts." I teach at a university with a "liberal arts" requirement, and I know from experience the battles to have a class listed as required (or optional) mix issues of academic politics and teaching philosophy. They can make or break particular classes, or entire programs.

A recent reconsideration of "liberal arts" (note: not the liberal arts) is available at the link below. What began as a series of conversations on a blog has been refined to a short book. The contributors go out out of their way to declare their list is not canonical, but here's their table of contents:

Introduction Timothy Carmody, Robin Sloan vii

Attention Economics Andrew Fitzgerald . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Brevity . . . . . . . . . . Gavin Craig . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Coding and Decoding Diana Kimball 8

Creativity Aaron McLeran 12

Finding Dan Levine . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16

Food Gavin Craig, Theresa Mlinarcik 18

Genderfuck . . . . . . . . Laura Portwood-Stacer . . . . . . . 22

Home Economics . . . . . . Jennifer Rensenbrink . . . . . 24

Inaccuracy . . . . . . . . Alex Litel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Iteration . . . . . . . . . Robin Sloan . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

Journalism . . . . . Timothy Carmody, Matt Thompson 34

Mapping . . . . . . . . . . Jimmy Stamp 36

Marketing Matt Thompson 40

Micropolitics Matt Thompson 42

Myth and Magic . . . . . . Tiara Shafiq 44

Negotiation . . . . . . . . Matthew Penniman . . . . . . . . . . 48

Photography Timothy Carmody 52

Play Matt Thompson 56

Reality Engineering . . . . Rex Sorgatz . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58

Translation Rachel Leow 62

Video Literacy Kasia Cieplak Mayr-von Baldegg . . . 66

About the Contributors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71

So, what do you think? What needs to be added to the list of liberal arts? What needs to be dropped? Is there a place for what we teach?

08 July, 2009

Drugs for fun and profit

The UN's 2009 World Drug Report is out. I'm pleased to report they acknowledge the limitations in their methodology. I'm amused--but not surprised--to see the response to the argument that "the drug war isn't working" is to increase enforcement. At least they want to prioritize the producers and distributors.

Conventional force structure and asymmetrical conflict

A thoughtful article asks a question I never thought I'd see in Naval Proceedings: why do we need a navy?

If "the naval era" is defined as the era of sea control, it ended in 1945—the last year of Fleet-size combat operations. Because the most recent sea battle worthy of the name occurred in October 1944, we are now into the seventh decade of the post-naval era.

The global war on terrorism is essentially a rifle fight. As much as partisans rankle at the notion, navies are largely irrelevant to its conduct, and the Air Force has been marginalized. In fact, unmanned aerial systems represent the growth industry, approaching the importance of manned aircraft. Meanwhile, the air superiority mission is nearly extinct: American pilots have shot down only 55 hostile aircraft in 36 years, the last one in 1999.

But the problem extends far beyond hardware to the fundamental realm of roles and missions. In a revealing document, the Department of Defense does not consider conventional warfighting a priority-land, sea, or air. In fact, the 2006 Quadrennial Defense Review listed four missions under "Operationalizing the National Defense Strategy":

- Defeating terrorist networks.

- Defending the homeland in depth.

- Shaping the choices of countries at strategic crossroads.

- Preventing the acquisition or use of weapons of mass destruction.5

An inbound question, low and fast out of left field: If not even DOD is concerned about conventional warfare, why do we persist in building a warfighting Fleet?

One of the "disadvantages" of technical and numerical superiority is that other people refuse to play by your rules. When direct experience dies, so does expertise. Some things can't be taught from a book. Even in a world of virtual reality training systems, the political elements--and the knowledge that it really isn't the "real" thing--lead to scenerios and assumptions increasingly divorced from reality. Then, when the real thing comes along, everyone is surprised. The questions become who will learn faster, and how much can they afford to lose while they are learning?

The Duck of Minerva waddles at midnight

I'll still be posting here, but it's always worth the time to check out the Duck for more insights (and controversy).

This is going to be fun.

05 July, 2009

Saudis and Israelis

There's an old saying that countries don't have friends, only interests. Like many old sayings, there's a germ of truth in it. And while the enemy of my enemy is most assuredly not my friend, he may be someone I can work with to achieve a common end. Case in point:

The head of Mossad, Israel’s overseas intelligence service, has assured Benjamin Netanyahu, its prime minister, that Saudi Arabia would turn a blind eye to Israeli jets flying over the kingdom during any future raid on Iran’s nuclear sites.

Earlier this year Meir Dagan, Mossad’s director since 2002, held secret talks with Saudi officials to discuss the possibility.

The Israeli press has already carried unconfirmed reports that high-ranking officials, including Ehud Olmert, the former prime minister, held meetings with Saudi colleagues. The reports were denied by Saudi officials.

“The Saudis have tacitly agreed to the Israeli air force flying through their airspace on a mission which is supposed to be in the common interests of both Israel and Saudi Arabia,” a diplomatic source said last week.

The countries don't have formal diplomatic relations, but that doesn't mean much--especially in a part of the world that's noted for deal-making, deception, and war. The Saudis would have to pay a political price, and they would have to accept the risk of playing a battlefield in a regional war. The move is a threat to the regime on several levels. However, the threat, especially if it is denied by the governments involved, could rattle the Iranians, and both Israel and Saudi Arabia have reason to consider that a good thing.

02 July, 2009

The Korean War is underway

But don't panic about it. An op-ed in the WSJ points out that since the North Koreans announced in 2003, 2006, and as late as May 26th this year that the Armistice is no longer binding on them, it means it is no longer binding for the UN (US) forces, either.

I doubt we'll see American ships fire on North Korean any time soon, but legally the US is within its rights to do so.

Perhaps North Korea should reconsider its position on the Armistice?

30 June, 2009

The American military budget (and I use the word "budget" loosely)

I teach American foreign policy, and every semester I run into the problem of trying to estimate how much money the government spends on the military. So I'm glad to see Mother Jones running a series on the budget. For a start, see what happens if you add other military expenses (like the Coast Guard role in the DHS, or the nuclear weapons facilities under the DoE, but not Veterans Affairs).

This doesn't include budgets for the intelligence community (other than those hidden within the DoD budget), so the total funding for "national security" is higher.

A glass half full in Afghanistan

Bill Lind does his typical excellent job analyzing the policy changes initiated by General McChrystal in Afghahistan. My favorite: shifting the official measure of effectiveness from "number of militants killed" (i.e., body counts) to "the number of Afghans shielded from violence." It's harder to estimate, but at least it recognizes what success is supposed to be.

Lind proceeds to a review of many of the structural problems that stand in the way of being as effective (as possible) in Afghanistan.

In sum, General McChrystal faces a full plate. His most difficult challenges are internal, in the form of a flawed military instrument, inadequate doctrine, a neo-liberal Establishment drunk on COIN juju and strategic objectives no commander can attain. Internal challenges are often harder to overcome than those posed by the external opponent, because potential fixes run into the immovable object of court politics.

As an Army friend put it to me, until these and similar internal challenges can be met, our efforts in Afghanistan are like trying to get somewhere by riding faster on an exercise bicycle.

Faster, faster!

Defense and the National Interest » On War #309: Going Nowhere Fast

China has its own problems

A story by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard includes this warning from Fitch Ratings. Fitch is an international credit rating agency, as well as one of four Nationally Recognized Statistical Rating Organizations (NRSRO) (the big ones are Moody's and Standard & Poor's) designated by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Unlike the big two, Fitch warned the market on the constant proportion debt obligations (CPDO) with an early and pre-crisis report, and its reputation has grown accordingly.

China's banks are veering out of control. The half-reformed economy of the People's Republic cannot absorb the $1,000bn (£600bn) blitz of new lending issued since December.

Money is leaking instead into Shanghai's stock casino, or being used to keep bankrupt builders on life support. It is doing very little to help lift the world economy out of slump.

Fitch Ratings has been warning for some time that China's lenders are wading into dangerous waters, but its latest report is even grimmer than bears had suspected.

"With much of the world immersed in crisis, China appears to be one of the few countries where the financial system continues to function largely without a glitch, but Fitch is growing increasingly wary," it said.

"Future losses on stimulus could turn out to be larger than expected, and it is unclear what share the central and/or local governments ultimately will be willing or able to bear."

Note the phrase "able to bear". Fitch's "macro-prudential risk" indicator for China threatens to jump from category 1 (safe) to category 3 (Iceland, et al). This is a surprise to me but Michael Pettis from Beijing University says China's public debt may be as high as 50pc-70pc of GDP when "correctly counted".

The regime is so hellbent on meeting its growth target of 8pc that it has given banks an implicit guarantee for what Fitch calls a "massive lending spree".

Bank exposure to corporate debt has reached $4,200bn. It is rising at a 30pc rate, even as profits contract at a 35pc rate.

Fitch traces the 2009 bubble to the central bank's decision to cut interest on reserves to 0.72pc. Bankers responded to this "margin squeeze" by ramping up the volume of lending instead. Over half the new debt is short-term. Roll-over risk is rocketing. China's monetary stimulus since November is arguably more extreme than the post-Lehman printing of the US Federal Reserve, though less obvious to the untrained eye.

No need to panic, but keep watching.

China's banks are an accident waiting to happen to every one of us - Telegraph

29 June, 2009

The world is an interesting place

Don't believe me? Let's open the newspaper. South Korea and Japan have agreed, according to the South Korean president, that they "will never tolerate" a nuclear-armed North Korea. This, despite the historic animosity between Koreans and the Japanese. On the other hand, what are they going to do about it? They call for implementing current UN sanctions, and "the need to deepen cooperation with China."

Where to look next: China. There are reasons why China wants and needs a North Korean buffer on its border, but only if NK isn't falling apart internally.

The US general in charge in Iraq reports the American troops are out of the cities, and the al Maliki government has taken the responsibility for urban security. One problem: General Odierno spoke of turning over authority to the "Iraqi Federal Government." There is no federal government in Iraq. It has been proposed, but the US blocked it, relying instead on centralization under al Maliki. For his part, al Maliki referred to the end of the American "occupation" of Iraqi cities. That plays well to the Iraqis, but it's a bit of a slap to the US.

One more example of how you can press for control by force, but you can't make someone your friend. Gratitude has a very short half-life among States.

Khomeni and Akmedenijad have done a thorough job of putting loyalists in charge of the army. Opposition leaders are falling over themselves to support the regime. The unrest now moves to discussions at dining room tables, and the economy continues to decline.

The Honduran ouster of president Zelaya is being described as a coup. Yet it was in defense of the Honduran constitution, in keeping with a Supreme Court finding that an upcoming referendum to allow Zelaya to run for a third term was unconstitutional. Apparently a lot of officers found themselves dealing with cognitive dissonance. What is superior: the orders of the Commander-in-Chief, or the law? On balance, they chose to back the rule of law.

What would the American military do under similar circumstances? I hope we never have to find out.

27 June, 2009

Conservativism I could live with

Jonathan Rauch , in a review of a book by Allitt that's going on my wish list, examines the rise and decline of the conservative movement into today's "zombie party." And what's that?

We know what happens when movements or parties continue to stagger forward after running out of ideas: They become zombies. Zombie parties are a recurrent feature of electoral democracies. Unable to articulate any coherent or workable governing philosophy, they mindlessly jab at cultural hot buttons, mechanically repeat hardwired tropes ("cut taxes, cut taxes, cut taxes"), nurse tribal resentments, ostracize independent thinkers. Above all, they feel positively proud of their doggedness. You can’t talk them out of it. Think of the Republicans in the FDR years, the Democrats in the Reagan years, the British Labour Party in the Thatcher period, and the British Conservative Party in the Blair period. Think of Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party for most of the past half-century, or France’s Socialists today. To get a new brain, zombie parties usually need to spend years out of power or wait until a new generation rises to leadership.

The current Republican Party--and, I dare say, the Libertarians (the Party, not philosophy)--could get a shamble-on part in the next George Romero movie.

"The refusal of so many of my fellow conservatives in the United States to adapt their thinking to facts and realities does not demonstrate their adherence to principle," David Frum recently wrote in Canada’s National Post. "It demonstrates a frivolous indifference to the responsibilities of political leadership." But Frum will tell you that his admonitions fall on deaf ears. "These days," he writes, "the question I hear most from political comrades is: ‘What the hell happened to you?’ " There are smart, modern people in the Republican Party and the conservative movement. But the movement is in no mood to listen to them.

History looks a little different from this perspective. For example, the Civil War is " 'a conflict between two types of conservatism.' Southern conservatives fought to conserve the South’s distinctive society, its time-honored traditions; northern ones, to conserve an indivisible, democratic nation-state." In our era "conservatives," in all their variety, were only able to keep it together as long as they did because of the fear of communism and the papering over of real ideological rifts.

The paper's gotten too thin. Tax cuts aren't always the solution. The growth of government probably can't be reversed, because for the most part people want a big government--so long as it is doing the right things.

Some conservatives do have ideas: Bruce Bartlett champions the idea of a Value-Added Tax (VAT) because, as well as raising funds, it can get government out of the micromanagement-by-taxation system (with all its inequities, inefficiencies, lobbyists, and corruption). Charles Murray builds on Milton's Friedman's call for a negative income tax, suggesting that all federal government transfer programs be cashed out and replaced by direct checks for $10,000 to every non-incarcerated American over the age of 21. Call it socialism, as I'm sure some conservatives will. Call it a Guaranteed Annual Income. Call it a Social Dividend (as Robert Heinlein alluded to in several of his novels). Labels don't matter. Getting a foundation of support to everyone, as a benefit of citizenship, equally, gets government out of the business of managing lives and playing political games with people's survival. Would it be perfect? Hell, no. This is politics. But it's certainly worth a look. And maybe, when the Republicans (or the Libertarians) have been wandering in the desert long enough, they'll find the courage to consider it.

23 June, 2009

Is poverty a violation of human rights?

Wil Wilkinson, blogger and philosopher, has a long and interesting post on rights. In turn, it has generated a long and interesting discussion in the comments section. He starts with the question of whether or not poverty is a violation of a (positive) right, and the more he looks at the question the more complicated it becomes. Along the way, he makes some fascinating connections. Check out this concluding paragraph:

The idea that there is something natural and inevitable, and therefore nothing objectionable, about the status quo global system of exclusive states is I think one of the ultimate barriers to the spread of legitimate human rights and the prosperity that entails. I think current debates over economic development and global justice seem so fruitless because they take for granted a set of illegitimate assumptions of which we have attained only a flicker of awareness.

How he gets to this point deserves to be read in full.

19 June, 2009

ACLU and Campaign for Liberty join against the TSA

Good news. When we get past the partisanship and bloviating, there are good people across "the political spectrum" (a stupid metaphor these days) who are learning they have a lot in common.

Raw Story » ACLU, Ron Paul’s Campaign for Liberty sue TSA over ‘illegal’ detention

Here's a report to read

A pretty good short review of some of what might be coming down the road. Best of all, the authors don't describe a single "future" but point out some of the directions current trends might take us.

Here's a report to avoid

The usual suspects make the usual arguments to reach the usual conclusions.

Strategic Failure: Congressional Strategic Posture Commission Report » FAS Strategic Security Blog

15 June, 2009

Medical care and the AMA

When insurance companies lobby and buy advertising, the general assumption is that they are doing so in their own interest. There may be a public interest as well, but its a secondary motive (at best) for the corporation. When a union supports a candidate with money and volunteers, we can also assume it is doing so in its own interest. While there may be a public interest, it is not the motive for the union's action. When a trade organization, like the National Association for Manufacturers, lobbies and buy advertising, it's most like that they are doing so in their own interest. The public interest, if any, is secondary.

And then there's the American Medical Association. The AMA is a trade association. Even among doctors it represents only a fraction of the population. According to Carol Paris, M.D., the AMA represents less than a third of American doctors. Of those it represents, half are retired.

When the AMA speaks for "America's doctors," it is--like any other lobbying group--looking out for its own interests. At best, those interests correspond to a fraction of the population of doctors. At worst, it's just looking out for itself. If (and I admit it's an ENORMOUS if) a single-payer system, or anything else, could significantly improve patient care at less cost, the AMA and its members would be the losers.

Whenever someone says they speak for "the doctors," or "the lawyers," or "the workers," or the businessmen," or "the students," ask for names, check identifications, and figure out who really benefits or loses, and by how much.

Electoral fraud in Iran?

Juan Cole makes a good case for it. At the very least, the numbers point to irregularities. Follow the comments for a range of opinions, as well as for what appears to be commentary from inside the country. Even if the election wasn't stolen, there seem to be a lot of Iranians who think it was--and that's what counts.

This could be the beginning of the fragmentation of the elite predicted by Bruce Bueno do Mesquita's models at the start of the year. From his TED talk:

Time to run?

A post from Lila Rajiva's excellent blog, as well as an article on LewRockwell.com, articulates something that has been making more and more sense to me. Perhaps it's just that I'm tired--perhaps a little bit depressed--but she's asking a critical question. Whatever the answer, it's time to think about it, and what it implies.

“Is it time to run?

That’s what I’ve been asking myself for three years now.

Before that, I thought it was simply a matter of finding a better place to live. A place that was quieter and cheaper. Where flippers and developers hadn’t taken over the neighborhood. Somewhere safe I could park my car on the street and not worry about it.

But by the time I found it, I also found that the thieves were inside the house, not on the street. There’s really no hiding from them. And no hiding from what they can do.

Our mene, mene, tekel upharsin is on the wall.

It’s time to run, not hide.

I mean that. We’re in the throes of an economic collapse of a kind last seen in the 1930s. The government is intent on grabbing control of whatever it can. American firms are dropping like flies. Unemployment is soaring. Debt is soaring. The money supply is soaring. Our foreign policy is a wreck – we have more enemies than we can count. We have a drug war on the borders, we have gang war in the ghettos, we have culture wars in the academy and media.

We have criminals in government.

The future isn’t any brighter. Subprime is only the first leg down. We still have a second wave of housing trouble in store, centering around commercial real estate and option ARM loans.

Gerald Celente, the CEO of Trends Research, wrote a piece last year predicting that by 2012 there would be food riots, tax rebellion, and revolution across the country. Celente has a good track record in the forecasting business.

Experts predict a 100% rise in prices across the board. In the best-case scenario, it will happen over ten years. In the worst case, it might happen within months….”

It's an integrated global system. In a lot of ways there may not be any practical places to run to (and now I know my thinking is depressed--it's time to pull back and work through it). However, some places will be better off than others. And a point she makes in a later post drives home the difference between practical and formal liberties:

The rest of the world has its own problems, true. Some of them are grave. But it's here in the US that activism is most sidetracked by partisan politics, insularity, grandstanding, and politically correct insanity. Really and truly, there are few countries in the world outside totalitarian regimes that are as conformist, pervasively and fundamentally, as this country.

I'd rather live under a benign despot that left me to my own devices from day to day, than in a democracy where I'm spied on and manipulated constantly. I may have theoretical rights, but much good they'll do for me if they're strangled at birth by spies, PR flacks, and thought-police.

Meanwhile, half these so-called rights don't exist any more, even in theory. A government that monkeys around with habeas corpus, privacy, bankruptcy procedure, eminent domain, and contracts is signaling loud and clear that it has no respect for the rule of law. It's telling you as plainly as it can that it's arbitrary. It's telling you that it's a mass state and not a constitutional republic. It's telling you that it's on the auction block.

Which part of all that hasn't got through to you yet?

Maybe like she's a little depressed, too. Or angry. But she's right to remind us that "America" is not a particular location, irregardless of what happens there. America is about an ideal. It is possible to be an "American" and never touch the soil of the United States. It's also possible to wrap oneself in the flag of the United States and be "American" in name only.

The good news is that the distinction between "America" the place and "America" the ideal makes it more likely that the America that matters will remain resilient at home and attractive to the rest of the world. This is a place where there's a tradition of distinguishing between the country and the State, and where the nation isn't a matter of blood but of vision. Although we can't (and shouldn't) impose an empire on the world, the spread of the ideal--voluntarily, the only way it can be done that is consistent with the ideal--could create something like the "empire of liberty" envisioned by Jefferson. A world that squares the circle by being both "global" and (increasingly) "liberal". To some extent Obama is playing to this in his attempts to accept criticism for the past and pledge to do better, and it seem to be working to remind people of the ideal. On the other hand, the actual policies aren't changing as much as the rhetoric.

12 June, 2009

Geopolitics and economics

Peter Zeihan of STRATFOR published a long essay on the natural advantages accruing to the United States, vis-a-vis any competitor. Either by dumb luck, or act of God (take your pick) the US has more usable land than anyone (for farming, or for other development), plus the bonus of an world's largest interconnected river system to provide cheap transportation, and three of the world's best natural harbors.

The real beauty is that the two overlap with near perfect symmetry. The Intercoastal Waterway and most of the bays link up with agricultural regions and their own local river systems (such as the series of rivers that descend from the Appalachians to the East Coast), while the Greater Mississippi river network is the circulatory system of the Midwest. Even without the addition of canals, it is possible for ships to reach nearly any part of the Midwest from nearly any part of the Gulf or East coasts. The result is not just a massive ability to grow a massive amount of crops — and not just the ability to easily and cheaply move the crops to local, regional and global markets — but also the ability to use that same transport network for any other economic purpose without having to worry about food supplies.

The implications of such a confluence are deep and sustained. Where most countries need to scrape together capital to build roads and rail to establish the very foundation of an economy, transport capability, geography granted the United States a near-perfect system at no cost. That frees up U.S. capital for other pursuits and almost condemns the United States to be capital-rich. Any additional infrastructure the United States constructs is icing on the cake. (The cake itself is free — and, incidentally, the United States had so much free capital that it was able to go on to build one of the best road-and-rail networks anyway, resulting in even greater economic advantages over competitors.)

Mexico and Canada have nothing approaching it. Until the US became regularly involved (and stationed) around the world, there was little need to guard the border, and no need for a large standing military. Capital could stay in private hands, invested in production.

Even with speculative bubbles, the US has managed to do pretty well--especially when compared to Russia and China.

Russia’s labor and capital resources are woefully inadequate to overcome the state’s needs and vulnerabilities, which are legion. These endemic problems force Russia toward central planning; the full harnessing of all economic resources available is required if Russia is to achieve even a modicum of security and stability. One of the many results of this is severe economic inefficiency and a general dearth of an internal consumer market. Because capital and other resources can be flung forcefully at problems, however, active management can achieve specific national goals more readily than a hands-off, American-style model. This often gives the impression of significant progress in areas the Kremlin chooses to highlight.

But such achievements are largely limited to wherever the state happens to be directing its attention. In all other sectors, the lack of attention results in atrophy or criminalization. This is particularly true in modern Russia, where the ruling elite comprises just a handful of people, starkly limiting the amount of planning and oversight possible. And unless management is perfect in perception and execution, any mistakes are quickly magnified into national catastrophes. It is therefore no surprise to STRATFOR that the Russian economy has now fallen the furthest of any major economy during the current recession.

And then there is China: Three long rivers, no connection between then, and no port at the mouth of the Yellow.

With geography complicating northern rule and supporting southern economic independence, Beijing’s age-old problem has been trying to keep China in one piece. Beijing has to underwrite massive (and expensive) development programs to stitch the country together with a common infrastructure, the most visible of which is the Grand Canal that links the Yellow and Yangtze rivers. The cost of such linkages instantly guarantees that while China may have a shot at being unified, it will always be capital-poor.

Beijing also has to provide its autonomy-minded regions with an economic incentive to remain part of Greater China, and “simple” infrastructure will not cut it. Modern China has turned to a state-centered finance model for this. Under the model, all of the scarce capital that is available is funneled to the state, which divvies it out via a handful of large state banks. These state banks then grant loans to various firms and local governments at below the cost of raising the capital. This provides a powerful economic stimulus that achieves maximum employment and growth — think of what you could do with a near-endless supply of loans at below 0 percent interest — but comes at the cost of encouraging projects that are loss-making, as no one is ever called to account for failures. (They can just get a new loan.) The resultant growth is rapid, but it is also unsustainable. It is no wonder, then, that the central government has chosen to keep its $2 trillion of currency reserves in dollar-based assets; the rate of return is greater, the value holds over a long period, and Beijing doesn’t have to worry about the United States seceding.

Meanwhile, Europe still can't get it's act together. Zeihan even claims that diversity of economic policies in Europe can be linked to geography.

Every part of Europe has a radically different geography than the other parts, and thus the economic models the Europeans have adopted have little in common. The United Kingdom, with few immediate security threats and decent rivers and ports, has an almost American-style laissez-faire system. France, with three unconnected rivers lying wholly in its own territory, is a somewhat self-contained world, making economic nationalism its credo. Not only do the rivers in Germany not connect, but Berlin has to share them with other states. The Jutland Peninsula interrupts the coastline of Germany, which finds its sea access limited by the Danes, the Swedes and the British. Germany must plan in great detail to maximize its resource use to build an infrastructure that can compensate for its geographic deficiencies and link together its good — but disparate — geographic blessings. The result is a state that somewhat favors free enterprise, but within the limits framed by national needs.

One-factor explanations are a little too perfect. If Charles Martel had not defeated the Muslim invasion, would France really be the same today? Rome managed to fall, despite having the same geography as during its rise. Today, a country that really wants to screw itself up--through military overcommitment, financial stupidity, or corruption--can overcome geographic advantages. I'm not naming anyone in particular, of course...

(I hope I haven't quoted too much of the original essay to constitute fair-use. If I have, please notify me and I will take it down.)

Don't forget Mongolia

It's a shame that the success stories don't get the press. Mongolia is one of the success stories, and neglect of what's been going on there is anything but benign. A recent essay from ISN brings us up to speed:

Mongolia has emerged in less than two decades as a vibrant, if not complicated, democracy, and stands worthy of enhanced United States and international attention and support. With its rich cultural and historical legacy, literate population and abundant natural resources, Mongolia has achieved steady economic growth and stands as a model of reform to North Korea to the east and the autocratic Stans to the west. Mongolia also is wedged strategically between a resurgent Russia and a rising China and borders a burgeoning Northeast Asia, the world’s economic powerhouse, and an expanding and, post 9/11, strategically viable Central Asia.

In its own right, Mongolia offers the international community a view of how a successful, relatively young democracy should appear. Compared to many other nations, Mongolia has progressed remarkably well. Yet too, its fragility in consolidation, highlighted by a need for governmental capacity, institutional and media reinforcement, reminds us of the responsibility of the United States and international community to better assist Mongolia and advance it on a path it deserves high praise for pursuing.

Mongolia is an outstanding global citizen. It led the newly emerging and restored democracies effort early in the decade, hosted United Nations dialogue on human security, supported international peacekeeping efforts, sited a major regional peacekeeping initiative, and offered itself as a venue for talks on easing tensions on the Korean peninsula, notable given its good relations with both North and South Korea. Foreign Minister Batbold in Washington has emphasized this week opportunities aimed at energy and economic cooperation, as well as on Korea.

****

...for all the fears of democratic rollback in Russia, Central Asia and elsewhere in post-socialist systems, Mongolians have embraced choice; an active, vocal, and sensible civil society has emerged, and Mongolians value choice.

Mongolia too is increasingly active in the regional and global economies and is increasingly interconnected. Internet cafes abound, and urban cable boasts connectivity to multiple channels in some dozen countries. With a young, literate and polyglot population, Mongolia sometimes feels less like a Northeast Asian outpost and more like the Netherlands, Belgium or a Chinese or Korean small city.

In spite of these pluses, Americans have been less than steady investors. Post-transition, Mongolians expected heady US investment, but Russia, China, the European Union, Japan and Korea are more dominant investors in Mongolia. It is time to open necessary doors to stimulate the Mongolian-US economic relationship.

This week, Foreign Minister Batbold had the unfortunate task in Washington of informing US Secretary of State Clinton that Mongolia would need to re-direct $188 million in U.S. infrastructure development aid aimed at rail improvement -- part of the $285 million Millennium Challenge grant awarded in 2007 -- given Russian objections. Russia has a fifty percent stake in the railway.

This should concern Americans, as Mongolia finds itself more vulnerable to the influence associated with foreign moneys, especially from Russia and China, which jockey to secure preferential controls in vital extractive industries and within joint ventures. Mongolia struggles with these trade-offs, and to this end the United States and its foreign business community could do well by assisting Mongolia in its strategic diversification

We should remember this as Mongolia continues on its democratic path and swears in President Ts Elbegdorj, who studied at Harvard’s John F Kennedy School of Government. President Elbegdorj rides into office on an Obama-like pledge to provide Mongolians change they can believe in and grow their living standards. Remarkable too was the quick concession of his opponent, President N. Enkhbayar, who realized that not doing so might result in political violence like that that flared in July 2008. This week, Enkhbayar pardoned women and youth embroiled in last summer’s unusual violence. Both sides deserve credit for this smooth transition of democratic power.

There are natural limits to what the US can do. The geographic facts are working against the Mongolians, as they balance two major powers on their borders with expansionist tendencies and a history of dominating their lives. Yet the Mongolian students I've met (not a random sample, I admit) have been among the most intelligent and caring and sensible people I've ever known. They deserve every break they can get.

Cycles and reforms

There's a very good discussion at The Baseline Scenerio (an all-around source for thought on the financial crisis). The short form: the US has done as well as it has because of the rule of law, but this has been undermined on more than one occasion by corruption and the concentration of power. Although there can still be "banana booms" (I love that term--comparing the current structure to banana republics), they aren't sustainable. These problems have led to course corrections in the past (under Johnson, TR, and FDR), but it isn't easy, and the reform period has averaged five to ten years. If it can't be fixed, we are doomed to a cycle of "oligarchy-boom-bust-oligarchy".

Global Crisis And Reform: Starting A Long Journey « The Baseline Scenario

10 June, 2009

Somalia is anarchy

Recommended reading: A correspondent in Mogadishu describes what it is like to live in a place that's been without a functioning State for 20 years. On the one hand, it looks like hell. On another, it's fascinating to see how people have done as much as they have to make it work.

Somalia: one week in hell – inside the city the world forgot | World news | The Guardian

09 June, 2009

CFR panel on the global consequences of the financial crisis

Is it good news for the US? A May 12th panel discussion included several scenerios, but in general it was optimistic. From Joe Nye:

To what extent has this crisis changed our views of what will be the relationship between the major powers in 10 to 20 years time? And when it first broke, the conventional wisdom -- Steinbrueck, the German finance minister, said this is the end of American dominance. Putin -- not Putin, Medvedev followed suit. Even my friend Michael Ignatieff, who's going, we hope, to become prime minister of Canada, said now that American power has reached high noon, Canada should be adjusting its policies elsewhere.

I think all this is wrong-headed. It's a big mistake to draw long-term conclusions from short run -- I mean, right now, you just project a linear projection of where we are, it looks bad. In fact, even those short-run -- or those predictions that were made at the beginning of the crisis have already been falsified. Decoupling -- remember decoupling?

MEDLEY: Yes.

NYE: Well, that got knocked on the head. The crisis was supposed to be the crisis of the dollar. Well, what happened to the dollar? Up, not down.

And then you say, yes, but China's doing well -- 6 percent growth this year -- America, not. We're somewhere in the negatives -- 3 percent, let's say, negative. But, you know, what's interesting is the decline of China's growth rate from 10 percent to 6 percent is greater than the decline of our growth rate. And that means the time when China would catch up with the United States in overall economic size doesn't get closer; it gets further out. I mean, Goldman Sachs's famous 2040 when they catch up, then they shortened it to 2027 -- well, you know what? It's going back to 2040.

On the other hand, Phil Zelikow does a very good job of reminding people that structurally, it's not possible to keep everyone happy, and a lot of people aren't.

The basic international political economy that we're revisiting today was forged in the late 1970s and early 1980s. And I want to remind some of you who took economics of the famous Mundell-Fleming impossibility theorem. The Mundell-Fleming impossibility theorem, for which Robert Mundell, a Canadian economist, won a Nobel Prize, stated that there are three desirable things you might want to have. You might want to have capital mobility, free movement of capital. You might want to have stable exchange rates. And you might want to have national autonomy in controlling your monetary policy, basically national economic autonomy. Those are three desirable things. Mundell argued you can never have all three of those things. You can only have two of those three things; pick which two you want.

The Bretton Woods system was liberal in many ways, on trade, especially. It was not a liberal system for capital mobility. Capital mobility was government-brokered and highly limited. This began to erode in the 1960s, and it was a system beset by constant crises, the -- no need to go into details. And therefore -- because what had happened is they resolved Mundell's theorem by saying, "We're going to sacrifice capital mobility to have stable exchange rates and national autonomy, because we're going to use national Keynesianism, and we want to have the freedom to do that." And then that system broke down and collapsed in the early 1970s.

What replaced it? What replaced it was a new solution to the Mundell theorem in which you sacrifice national autonomy to a very large degree. You get more stable exchange rates -- somewhat stable exchange rates and a high degree of capital mobility. That -- there were big crises that tested the formulation of that, bracketed by -- from the British IMF crisis of 1976 to the Third World debt crisis and Mitterrand's famous u-turn of 1982. Now, that is important.

The question is, today, are we going to revisit that solution to the Mundell theorem? And the place where it is most likely to be revisited is not the United States, nor in East Asia, which relies on capital mobility. It is in Europe. It is in Europe where, actually, it was tested most severely in the late '70s and Mitterrand's France, and it is in Europe where it may be tested again. Mitterrand made the u-turn in 1982 after he tried a national Keynesian approach. He was broken, basically, by the Germans and the European monetary system, by the way, who had also disciplined the Americans during the Carter administration. And finally the Americans gave in and appointed Paul Volcker in 1979 after they had bucked against Europe, for those of you who think the Americans always make the rules. The Germans really had been the anchor throughout, partly because of their continuing coalitions that always had the Free Democrats as a critical partner playing a governing role in their economic policy.

Now, the Germans are still actually the anchor in the way Europe has been approaching it and -- (inaudible) -- hard-money policy Europe has generally been adopting lately. That's being tested right now in Germany and in European politics. Not only are there the East European problems, which have gotten some attention. In some ways, I'm more worried about Southern Europe over the -- over the near term. But look at what's happening in German politics, per se. Oskar Lafontaine and others are now joining hands with some of the old former East German communists and they're making a square assault on the whole fundamental premises of the social market economy that has governed the German economy for the last generation. They're going after the Mundell theorem.

If and when Germany cracks, where is France? Then where is Europe? And where is the system as a whole?

The other key, everyone seems to agree, is whether China will grow its internal market to the point that some dollars are flowing out, rather than just in. This is seen as being a "responsible stakeholder" and a necessity for a country that has no alternatives to holding dollars. I'm not so sanguine about it.

04 June, 2009

Comparing Argentina and the US

Both countries opened up the west, the US to the Pacific and the Argentines to the Andes, but not in the same way. America favoured squatters: Argentina backed landlords. Short of cash, Buenos Aires found the best way to encourage settlers was to sell in advance large plots in areas yet to be seized from the native Americans. But once the battles were won the victors were exhausted, good farm labourers in short supply and the distances from the eastern seaboard to the frontier vast. Most of the new landowners simply encircled wide tracts of grassland with barbed-wire fences and turned them over to pasture.

Thus was privilege reinforced. European emigrants to Argentina had escaped a landowning aristocracy, only to recreate it in the New World. The similarities were more than superficial. In the 1860s and 1870s, the landowners regarded rural life and the actual practice of agriculture with disdain. Many lived refined, deracinated lives in the cities, spending their time immersed in European literature and music. The closest they came to celebrating country life was elevating polo, an aristocratised version of a rural pursuit, to a symbol of Argentine athletic elegance. Even then it took an elite form: the famous Jockey Club of Buenos Aires. By the end of the 19th century some were sending their sons to Eton.

America’s move westwards was more democratic. The government encouraged a system of smaller family holdings. Even when it did sell off large tracts of land, the potential for a powerful landowning class to emerge was limited. Squatters who seized family-sized patches of soil had their claims acknowledged. US cattle ranchers did not spend much time boning up on the entrance requirements of elite English schools. And as well as raising cattle, the western settlers grew wheat and corn. By the 1850s, the US was importing a quarter of a million immigrants a year.

Immigrants came to Argentina as well, but they came later and with fewer skills – largely low-skilled Italians and Irish. In 1914, a third of Argentina’s population was still illiterate. America imported the special forces of British agriculture, and in addition a large number of literate, skilled workers in cloth and other manufactures. Meanwhile, Argentina had more land than it could efficiently work. But it was well into the 20th century before the rot in the foundations was apparent.

Piracy: buisness is booming

Is mind reducible to brain states?

29 May, 2009

North Korea and Plan 5027

20 May, 2009

Odds and ends

(1) Chris Goodall connects what he describes as the "complacency" over climate change to the irrational tendencies of the human mind: estimation bias, overoptimism, the need for a visible enemy, etc. I'm not entirely convinced. In at least some cases, these biases have proven to be useful. Would you have been born if your parents weren't suffering from irrational opimism? Is it possible that these biases (which no doubt exist) are still useful? His more telling point is that things that are rational for individuals may not be rational for collectivities. It makes sense to take care of myself and my family, rather than rely on an assumption that everyone else--now and for all time--will behave in a way that will be in my long-term best interest. Besides, who's to say what my best interest is? Goodall sees the problem, but his "solution" has problems all its own:

If I had to guess whether humankind could possibly ever agree to take substantive action on climate change if the worst effects only really began in a hundred years time, I would be pessimistic. We would have to rely not on economics or even traditional moral arguments, which have all the weaknesses I have tried to identify above, but on what is essentially a religious faith – a view that respect for the Earth demands that we allow it to stay largely as it is. [emphasis mine] There's no doubt that this is an important force in human thinking, even among people without conventional theism. After all, we do all seem to care a lot about a few thousand polar bears of no direct economic value. But I strongly doubt whether the quasi-religious strand in our thinking is powerful enough to get us to take the really radical actions that we need.Is a theology of strong ecology the only (or best) way to go?

(2) The bbc reports that the Japanese economy is declining faster than it ever has since the record-keeping began in 1955. (If it were to continue at this rate, we'd see an annual decline of 15% of GDP.)

(3) Jesse Ventura gets back to basics on Fox news: waterboarding is torture, torture is illegal, we claim to be a nation under the rule of law, and if we really mean it about the law there are some senior officials who deserve to be prosecuted. The video of the argument on Fox and Friends is priceless.

(4) And the good news from the FAS, showing the decline in Russian and American nuclear arsenals:

25 April, 2009

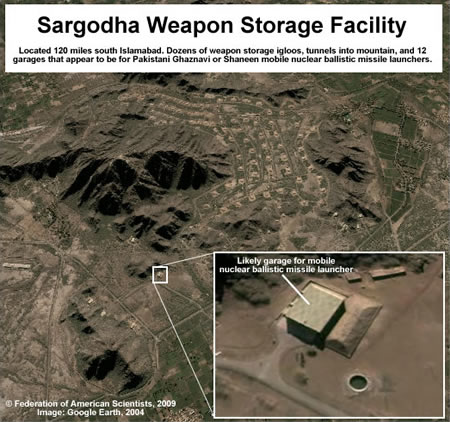

A reminder of why to worry about Pakistan

According to Secretary of State Clinton, Pakistan's nukes are "widely dispersed in the country — they are not at a central location." And while this might be a good way to protect against a first strike and maintain a retaliatory force, it also opens the door to losing some weapons to local guerrillas. The Taliban doesn't need to obtain all the weapons in order to be dangerous.

Concern Over Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons » FAS Strategic Security Blog